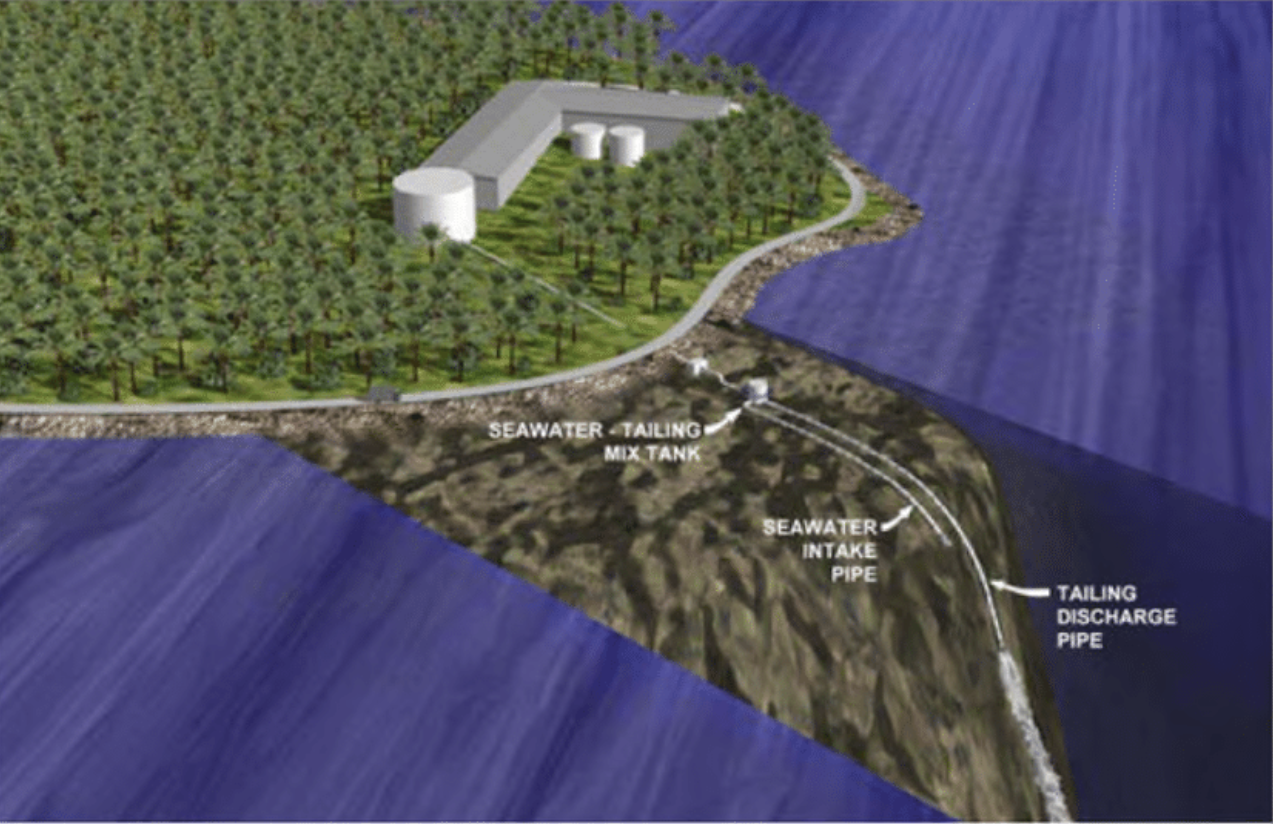

The Wafi-Golpu gold and copper mine proposal details wide-reaching mine infrastructure, including a 103 kilometre pipeline that stretches across the Morobe district, through the second most populated city of Lae, into the villages of communities living along the Huon Gulf coast, and ending up being dumped as tailings into the Huon Gulf ocean in a method known as ‘Deep Sea Tailings Placement’, or ‘DSTP’.

Tailings are waste materials from mining that consist of toxic materials such as mercury, uranium, lead, petroleum byproducts, sulfuric acid and cyanide.

Across the mine’s initial lifespan of 28 years, these tailings, or mining waste, are proposed to be transported through the earthquake-prone city of Lae, across floodplain-prone agricultural lands such as near Wagang Village, at a quantity of 360 million tonnes (or more than 1 trillion litres).

Any failure of the 103 km pipeline will cause environmental destruction and chemical contamination of the rivers, food and water sources, agricultural sites, and sacred sites along the DSTP pipeline and the outfall area. It can result in loss of human life.

With ample research confirming this risk, the companies are still proposing to build the pipeline along the earthquake-prone city of Lae, and the floodplain villages along the Huon Gulf.

The companies’ own independent researcher, Professor Ralph Mana, has been a strong public critic of the DSTP proposal for the Wafi-Golpu project, saying that his research suggests that less than 10 per cent of total tailings will reach the Markham Canyon, a figure which is shockingly inconsistent with the Wafi-Golpu Project’s assessment in its Environmental Impact Statement, which proposes that 60 per cent will reach the Markham Canyon. Professor Mana cites that the proposed offshore site is inappropriate and that the mining waste material will spread 30 km in every direction due to ocean currents.

The use of Deep Sea Tailings Placement (DSTP) is not legal in Australia, and is used by only 15 mines in the world. The method of dumping waste into the ocean has been banned in many countries, and is being phased out worldwide, because of the many risks associated with it.

Wafi-Golpu would be one of the largest copper and gold mines in the world and one of the largest ever in Papua New Guinea. This means that it will also generate huge quantities of waste.

How much waste will the Wafi Golpu pipeline transport?

The mine is estimated to release 360 million tonnes of mining waste over 28 years - and potentially more. Once up and running, the mining contract could continue and it could be allowed to run for 50 years or longer.

Also, the companies have estimated a much higher amount of reserves within the Wafi-Golpu deposit. If the companies access these reserves, there could be 1 billion tonnes of mining waste.

This is roughly the same amount of tailings that Ok Tedi has dumped into the Fly River across its history until now. The Wafi Golpu mine could be the Ok Tedi of the Sea.

Wafi Golpu Exploration Site. Image sourced: Newcrest Mining, 2022.

Where will the mining waste be dumped?

The mining waste will be dumped into the ocean off Wagang Beach, approximately less than 1km from the shoreline.

Is the mining waste toxic?

The mining waste from Wafi Golpu will include arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, mercury, zinc, selenium, lead, manganese, sodium, nickel, vanadium, aluminium, silver, calcium, iron and potassium.

We do not know what levels of each mineral are present in the tailings as this has not been made public by the company. However, exposure to heavy metals can be very damaging to human health.

For example, exposure to manganese can have impacts on the brain and nervous system. The companies estimate that manganese levels of fish will double from their current levels after DSTP begins – and while still within guideline limits, this is still concerning.

The mining waste that the companies plan to be dumped into the sea may also include processing chemicals that were used to process the minerals. Many of these chemicals are toxic to aquatic life and can have impacts on human health. There does not appear to have been a scientific study of the impacts of these chemicals by the companies, and no disclosure of how much will be dumped into the ocean.

This means that there is limited information on the exact risks and impacts that could happen if any part of the 103 kilometre pipeline cracks or breaks. It means that the companies proposing this mine, and the pipeline that will carry its waste, are not able to detail the chemicals that could potentially cause environmental destruction and chemical contamination of the rivers, food and water sources, agricultural sites, and sacred sites along the DSTP pipeline and the outfall area.